The Sound

Hi there!

In this series, interested readers can find individual biographies of the historical characters depicted in my novel The Sound.

The story behind The Sound

The Astrolabe in 1827

“It struck me there must have been some bad work going on there.”(12)

Major Edmund Lockyer arrived in King George Sound on the brig Amity on Christmas Day 1826 to annex the western part of New Holland for the British Crown. Captained by Thomas Hansen,(13) the Amity was laden with the resources for the new settlement including skilled-convict labour, soldiers, sheep, seeds and poultry. As Commandant, it was Major Lockyer’s contract to construct and govern what was essentially to be the beginnings of a military outpost and to guard against French occupation.(14)

Whilst sailing into the Sound, Lockyer saw smoke from a fire on Michaelmas Island and noted that he thought a sailor may have been marooned there. The next day he sent a boat to the island and his crew returned with four Aboriginal men, some with cutlass scars across their throats and other evidence of battle upon their bodies. Lockyer had reported thus far spending a harmonious day meeting and hunting with some Menang men. Therefore he must have been shocked as the collective mood of these men swiftly became antagonistic once they had held a meeting with their countrymen who had been marooned on Michaelmas. Several of the men left as a group and called away any Menang men who were with Lockyer. They then speared the Major’s only blacksmith Dennis Dineen, in what appeared to be retribution for an unexplained, historic insult. To his credit, Lockyer ordered that no retaliatory action be taken. The next day when he explored Green Island in Oyster Harbour, Lockyer discovered the desiccated body of an Aboriginal man lying close to a partially completed raft. At this point, Lockyer realised that he had sailed into a feud between the Menang and an unknown band of seamen, who must have taken the Menang men to Green Island. “It struck me there must have been some bad work going on there; the natives have no Boats; they never venture above Knee deep in the water.”(15)

Two weeks after the Amity’s arrival his suspicions were confirmed when eight sealers in a whaleboat slipped into Princess Royal Harbour.(16) The sealers boarded the Amity and asked Lieutenant Festing for victuals. Festing referred them to the Major, and the boatsteerer(17) William Bundy gave Lockyer a note from his employer Mr. Robinson, stating that the writer would ‘pick up the bill’. The seamen “proved to be part of a Sealing Gang, the Boat belonging to a Mr. Robinson of the schooner Governor Hunter(18), with some of the crew of the schooner Brisbane, the Master having gone off and left these men on the Islands here.”(19) In contrast to the Major’s ethnically homogenous party consisting of English nationals, only half of the sealers he met that day were of Anglo Saxon heritage; the other four he variously described as ‘a Sydney Black’, ‘a Black Man’, and a ‘New Zealander’.(20) This diversity of origins was common in Southern Ocean sealing communities at the time.

Major Lockyer invited the sealers to eat and stay aboard the Amity that night. On the morning of Thursday the 11th of January, he sent for the sealers and interviewed them in his camp. Their testimonies, in particular that of William Hook, detailed the killing of the man on Green Island in October 1826 and the abduction of several Menang women, and prompted Lockyer to request that Festing detain the sealers and their boat. Consequently, that night the Amity became the first watch house in Western Australia. The next day, Lockyer sent for William Hook and interviewed him again. He quizzed Hook on his understanding of the “nature of an Oath and the consequence of swearing to what was not true”(21) and when he was assured that William Hook understood, he swore the sealer to his information and made him sign the statement.(22) This statement, sent as part of Lockyer’s report to the Colonial Secretary, is the only known primary source that documents the sealers’ crimes of October 1826.

In the evening of October 12th, 1826, eight weeks before Lockyer arrived, a sealing gang from the Governor Brisbane sailed a whaleboat across King George Sound to come alongside the French expedition ship Astrolabe. After a rough crossing from Trinidad, Captain Dumont d’Urville had stopped in King George Sound to give his crew a rest and mend the rigging. The sealers told the captain they’d been abandoned, were living from their fishing alone, and had settled on Breaksea Island in the Sound. Captain d’Urville offered them the night aboard as well as ship’s biscuit and brandy. In return the sealers brought to the table muttonbirds, natural history and information on safe anchorages. The sealers complained to d’Urville of “a great deal of the hardships and privation they had endured while waiting for a boat to take them off.”(23)

Four Breaksea Islanders took up d’Urville’s offer of a working passage to New South Wales. The remaining five declined; d’Urville perceived his offer as being “coldly received.”(24) This led d’Urville to thinking that most of them were escaped convicts who preferred to avoid the eastern states and the law. (Some of the English sealers had a living memory of the Napoleonic war between England and France and this may have influenced their attitude.) D’Urville expressed his distrust of the sealers, writing that he only gave them permission to stay aboard because he worried they would otherwise find his shore camp that night and he wanted to get a measure of the men first. Still, he showed some private admiration in his journal: “What an extraordinary fate for eight Europeans to be abandoned like this with a frail skiff on these deserted beaches and left entirely to their own resources and industry!...”(25)

Footnotes

12 Historical Records of Australia: Despatches and Papers Relating to the Settlement of the States: Tasmania, April – December, 1827, West Australia, March 1826 – January, 1830 Northern Territory, August, 1824 – December, 1829: Series 3, Vol. 1. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Department, 1923, p. 466 (Hereafter referenced as Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol.1)

13 Hansen, K., The Life and Times of Captain Thomas Hansen 1762-1837, Watermark Press, Auckland, 2007, p. 23.

14 Although Major Lockyer was acting on Governor Darling’s concern that the French were preparing to annexe New Holland as a penal colony, Leslie Marchant maintains they had no intention of doing so. “In reality there was no basis for that fear. Major Lockyer’s action in coming to Albany did not thwart the French. The French then no longer had serious intentions of challenging the British there.” Marchant, L., France Australe, Scott Four Colour Print, Perth, 1998, p. 246. However Edward Duyker, in his biography of d’Urville argues that surveying King George Sound was a deliberate aspect of the Astrolabe’s ‘unofficial’ expedition. Duyker, E., Dumont d’Urville: Explorer and Polymath, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2014, p. 192.

15 Lockyer, H.R.A.III, Vol. 1, p. 466.

16 For Lockyer’s reports to the Colonial Secretary during this period see H.R.A., III, Vol. 1, pp. 457-537.

17 ‘Boatsteerer’ is a whaling term. In a sealing gang the boatsteerer was the leader of that boat’s crew.

18 Here, Lockyer erroneously names the Hunter the Governor Hunter. The Governor Hunter was wrecked in 1819.

19 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 468.

20 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 468.

21 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 469

22 For William Hook’s statement see Appendix 1, or Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

23 Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. An Account in Two Volumes of Two Voyages to the South Seas, Vol. 1 Astrolabe 1826-1829, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 1987, p. 31. (Hereafter referenced as Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987.)

24 Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 31.

The story behind The Sound #2

Channel Mouth by Catherine Gordan

The Governor Brisbane, owned by Kemp and Co. had brought approximately sixteen sealers to western New Holland in February 1826 as part of a sealing operation.(26) According to the sealers’ testimony to Captain d’Urville, Captain Davidson dropped six crew at Coffin Bay and another eight at Middle Island adjacent to what is now called Esperance. Davidson then sailed the schooner to Timor. By June 1826, the Hobart Town Gazette reported that the schooner was seen off the North West coast “with only two men and the master on board.”(27) By January authorities at Batavia had seized the ship and put the men under guard, suspecting them of piracy.(28) The Governor Brisbane did not return to King George Sound to pick up the sealers.

At this point I must mention a discrepancy with recorded dates. Because sealing operations were often covert, especially as seal resources were scarce in the east, their destinations were not always recorded. Some of the Breaksea Islanders told both d’Urville and Lockyer that they had been abandoned in the west for eighteen months, which would mean they arrived in the west in 1825. Others said they had been in the west for seven months. It is likely that the Governor Brisbane ventured west the previous sealing season of 1825. Advertisements placed by the owner of the Governor Brisbane in Hobart in August and September 1825, requiring an expedition fit-out and warning creditors of the crew members’ imminent departure, indicates that Kemp and Co. were planning a journey to New Holland that year.(29)

Another sealing operator deposited small groups of sealers on islands along the south coast in 1826 and, like the Governor Brisbane’s captain, the owner of the Hunter George Robinson also failed to return for his crew. However tracing the movements of the Hunter’s sealing expedition west is easier than tracing that of the Governor Brisbane. A paper trail of increasingly irate letters between authorities in Mauritius, New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land – regarding the return of five Pallawah women, one child and several dogs from Mauritius to Van Diemen’s Land – includes a signed contract between three sealers and the owner of the Hunter, and statements regarding the Hunter’s entire western sojourn before the sealing gangs were abandoned.

After taking several crew on at King Island in Bass Strait, the Hunter sailed to King George Sound where the ship’s owner George Robinson deposited crew and a boat to ‘procure seal’. According to newspapers of the time, in September 1826, the Hunter then sailed south to the Isle of St Paul and Amsterdam Island: isolated and barren Southern Ocean islands. There, Robinson and Captain Craig left the two sealers, Proudfoot and Paine, with limited supplies and later attempted to land four more men and provisions. Due to dangerous winds and the ship being sent to leeward of the island, Craig decided to leave the Isle of St. Paul. Proudfoot and Paine were rescued from the subantarctic island nearly two years later. They had been landed without even a knife and survived by eating muttonbirds, eggs and wild celery. (30)

Footnotes

25 Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 31.

26 Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser, 26/08/1825, p.1.

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/2445859 (Accessed 10/06/2014)

27 Hobart Town Gazette, 10/06/1826, p.2.

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/8791207/68002 (accessed 09/11/09).

28 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 26/01/1827, p.3.

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/2448901/679182 (Accessed 11/08/09)

“Our Readers will not confound Mr. Baxter's schooner Brisbane of Sydney. Thomas Smith master, with Messrs. Kemp and Company's, the Brisbane of this Colony, which was piratically carried off by the master Davidson (formerly mate of the ship Phoenix) from Bass's Strait to Batavia, where it was seized by the Dutch Government, and Davidson and his guilty crew placed in confinement.” Hobart Town Gazette (Tas. : 1825 - 1827) 07/10/1826 p. 2. http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/8790797 (accessed 10/06/14).

29 Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser 26/08/1825, p.1 (Accessed 22 Jun 2015) http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page678911. Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser, 23/09/1825, p.1. (Accessed 22 Jun 2015) http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page678931.

Many thanks here to Ciaran Lynch who has helped resolve the discrepancy in the dates that the Governor Brisbane sailed from VDL.

The story behind The Sound #3

On reading the three sealers’ statements to the Chief Commissioner of Police in Mauritius, it becomes apparent that they had embarked at King Island, along with five Pallawah women, a child and several dogs, under the agreement with Robinson that they would also work on St. Paul’s. The fate of seamen Proudfoot and Paine are not mentioned in this document. Problems with broken rigging, sails and rapidly dwindling water and food supplies meant that Robinson decided to drop most of the crew at King George Sound to work the seal there and return to Van Diemen’s Land; the nearest port and chandler to replenish their supplies. The Hunter returned to King George Sound in March 1826 and left another whale boat with five men and presumably one or two Aboriginal women. They then sailed to Rodrigues Island near Mauritius. Captain Craig was quoted as stating that if he sailed into Mauritius and met a King’s vessel, “that the captain of the Man of War would not believe these women were free people”. So the three sealers, one child and five women were left on Rodrigues instead. (31)

The Hunter did not return to King George Sound. Because Robinson encountered financial difficulties and needed to sell the Hunter, he did not return for the abandoned men, women and children at the Isle of St. Paul or Rodrigues Island either. (32)

Two Pallawah women, a female child and a woman from the Cape Jervis area stayed in King George Sound with approximately sixteen male sealers. The crews from the Governor Brisbane worked their way from Middle Island to join the crew from the Hunter on Breaksea Island some time before October 1826. They roved the islands in whaleboats, hunting seal between the Recherche Archipelago to the east and the Swan River to the north, using Breaksea Island as their base. It appears from statements made retrospectively by the sealers that for a while they had friendly communications with the Menang people of King George Sound and that the two groups cooperated amicably in order to hunt and fish. Hamilton, one of the sealers who embarked on the Astrolabe, described the Menang to Captain d’Urville as “gentle people, kind and incapable of harm.” (33) However, this apparent mutually beneficial relationship was about to be exploited and then betrayed.

Footnotes

30 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 12/02/1829, p. 3.

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/497210?zoomLevel=1

31 In this thesis, I do not expand on the extraordinary journey of the five Pallawah women and one child who lived at Rodrigues Island and Mauritius, as I must remain focussed on events at King George Sound. Among others, academics Lynette Russell and Julie Gough have written extensively on this subject. Russell, L., Roving Mariners: Australian Aboriginal Whalers and Sealers in the Southern Oceans, 1790-1870, State University of New York Press, New York, 2012. Also see Appendix 5 for letters between the Port Louis Police Department, Mauritius and the Colonial Secretary of New South Wales. CSO, Port Louis, Mauritius. 1826 – 1827.

32 Details of the Hunter’s itinerary is from a letter of information received by the Chief Commissary of Police and signed by two sealers, December 1826. Archives of Tasmania #91. (CSO 1/121/3067).

The story behind The Sound #4

On October 25th 1826, the Astrolabe left for Port Jackson with four Breaksea Islanders aboard as crew. According to the testimony of Breaksea Islander William Hook,(34) the next day some Menang men approached John Randall, the boatsteerer from the Governor Brisbane, to go muttonbirding on Green Island, a tiny verdant island in Oyster Harbour. John Randall and James Everett instructed two sealers, Edward Edwards and William Hook, to take the Menang men out to the island and strand them there.

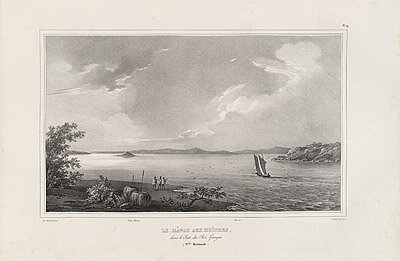

The Sound, by Louis de Sainson, depicts the crew of the Astrolabe atop Mount Adelaide. Green Island is just north of the channel into Oyster Harbour.

At dawn on the morning after the Menang men were marooned, four sealers went inland armed with cutlasses and guns. They were away all day and returned with four Menang women in the evening. Two of the women escaped that night, despite being tied together by their arms. The sealers then drew straws for the remaining two women. Samuel Bailey drew a long straw, as did George McGuiness. In the morning the sealers took the women out to Breaksea Island, ostensibly to imprison the captured women and escape Menang retribution.

The following day Randall sent Hook, Edwards and four other men to Green Island with a keg of water and as they approached the island, the Menang men rushed the boat. The sealers returned to the shore of what is now called Emu Point. Four ‘fresh hands’ rowed out to the island again, taking with them guns and cutlasses. When they arrived at Green Island a fight ensued between the sealers and the Menang men. Someone fired a gun but the Menang men persisted. The second shot killed one of the Menang men, who fell face-first into the water, “blood spouting out from both his sides.” (35)

On the third day of the marooning of the Menang men, Randall went out to the island himself. To illustrate the previously amicable relations and subsequent betrayal, Hook described the scene as: “At first the Natives hid themselves; but on seeing Randall who was a great favourite with them, they came out and kissed him.” (36) Randall took the four surviving men aboard his boat and left the dead body on the island. He was said to have intended on taking the men ashore at Emu Point but sealers later told Lockyer that “the shore was lined with mobs of natives and they could not in safety land these men on the main.” (37) It seemed that the ‘Natives’ were no longer ‘incapable of harm.’ Randall and the sealers took the Menang men to Michaelmas Island instead and abandoned them there, leaving them “making great lamentations.” (38)

Footnotes

34 The following recount of events is by William Hook, as recorded by Major Edmund Lockyer in his correspondence to the Colonial Secretary Alexander Macleay. Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

35 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

36 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

37 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 484.

38 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

The story behind The Sound #5

For eight weeks the Menang men remained on Michaelmas Island. They tended to the cutlass wounds on their throats and bodies and lit fires to communicate with their country men and women on the mainland. Tiffany Shellham speculates that the Michaelmas Island fire which Major Lockyer saw on his arrival was not the Menang men’s appeal for assistance but rather to alert their families on the mainland, warning them of an unknown ship entering the Sound.(39)

Rock Dundar, adjacent to Michaelmas Island

The channel between Michaelmas Island and Breaksea Island is prone to tidal surges and about eighteen hundred metres in width. They may not have been able to swim the channel but if they stood on the south side of the island and looked across the stretch of water to Breaksea Island, the Menang men would have been able to see the sealers’ camp and the two abducted countrywomen. At some stage in the eight weeks between the Astrolabe leaving and the Amity arriving, McGuiness took a female Menang captive to an island east of King George Sound and Bailey took the other Menang woman and a female child to Eclipse Island.

Lockyer’s subsequent attempts at procuring justice for the Menang population could be construed as a utilitarian act for a fledgling colony vastly outnumbered by their Indigenous landlords, as a ‘law and order’ campaign against the white men who lived on the very edges of society, and to assert his authority as first Commandant of King George Sound. The day after taking William Hook’s statement, he ordered that the Amity’s naval party go to Eclipse Island to rescue the Aboriginal child, the Menang woman, and to arrest Samuel Bailey.

With the exception of the Menang population, the people who gathered at King George Sound in 1826 were people on the fringes of their known worlds. By January 1827, the story of the three communities, Menang, sealer and coloniser, who collided and clashed in King George Sound in 1826, becomes frayed. John Randall sailed with his crew to the Swan River.(40) Lockyer left after one hundred days and was replaced by the second Commandant Captain Wakefield.(41) The sealer Samuel Bailey was sent to New South Wales to face justice for murder. William Hook was sent to testify against him. The men who had speared the blacksmith avoided the colony for fear of being recognised by Lockyer, and the Aboriginal girl was sent to New South Wales to face an uncertain future among strangers. The Pallawah women worked the islands with sealers to the east and the north of King George Sound, and eventually they returned to an uncertain future in the crucible of violence that was Van Diemen’s Land’s Black War.

Footnotes

39. Shellam, T., ‘Making Sense of Law and Disorder: Negotiating the Aboriginal World at King George’s Sound’, in History and Anthropology, Vol. 18, Iss. 1, 2007, pp. 75-88.

40. In 1837, Aborigines at Swan River described a boat carrying both whites and Aboriginal men up the river ten years previously, matching the crew of Randall and Pigeon or Robert Williams. Green, N., Broken Spears, Aborigines and Europeans in the Southwest of Australia, Focus Education Services, Perth, 1984, p. 46.

41. Hunt, D., Albany, First Western Settlement: Forerunners ~ Foundation and Four Commandants, The Albany Advertiser, Western Australia, no date, p. 25.

William Hook’s Statement

Below is William Hook's statement that he made to Major Edmund Lockyer in January 1827. His statement, signed with an X, is the text that forms the basis for my novel The Sound.

Historical Records of Australia, Series 3, Vol. 1, p. 473.

INFORMATION of William Hook, Native of New Zealand, Mariner and late belonging to the Schooner Brisbane of Hobart Town, touching the murder of a Male Native on Green Island, Oyster Harbour and King George’s Sound, and also forcibly taking away from the Main Land at Oyster Harbour four Male Natives, and landing them on Michaelmas Island in King George’s Sound, and there leaving them to perish, of the truth of which he, William Hook, voluntarily maketh Oath before Edmund Lockyer, Esquire, Major of His Majesty’s 57 Regt. Of Infantry, and Justice of the Peace of His Majesty’s Territory in New South Wales and Commandant of the Settlement at King George’s Sound, this Twelfth day of January, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Seven.

“That he, William Hook, being with the following persons at Oyster Harbour that composed the crew of a Boat employed sealing, John Randall Steersman, James Kirby, George Magennis and Samuel Bailey, with another Boat belonging to a Mr. Robinson of Hobart Town, and of which one Everitt was Steersman, the names of the crew he does not recollect, whilst there, had frequently been visited by the Natives, who were friendly, accompanying the Sealers fishing in their Boats, though the Native Women were never seen or came to the place where the Sealers were hutted.

That, about Eight Weeks ago, a French Man of War anchored in the sound and remained some time. That, one day after this Ship had left, Five of the Natives came to where their Boats stopped and requested to be taken to Green Island in Oyster Harbour to catch birds, when this Informant and another Man of the Hunter’s Boat, by name Ned, was ordered by John Randall and Everitt, the Boat Steerers, to take the Natives there and land them and come off, leaving them there, which they did; the Natives, perceiving the Boat going away, called out to the Informant to return, making all the signs possible for that purpose; but, having been ordered to leave them, Informant was afraid to act otherwise.

De Sainson's painting of Green Island and the channel at Oyster Harbour

Next day Randall set out, accompanied by Kirby, Magennis and Bailey, armed with Guns and Cutlasses, soon after five OClock in the morning, and returned about Four or Five in the Evening bringing with them Four Native Women; that during their absence Informant was ordered to stay and take care of the Boat; during the night, two of the women made their escape though the Sealers had tied them two together by the Arms; next Morning both Boat’s Crews again went off armed, leaving Informant and another to watch the Boats; in the Evening they returned saying they had not seen any of the Natives or the Two Women that had made their escape, but had found hanging to the Trees at their encampment a Pocket Compass and a knife that had been given to the Natives by the Captain of the French Ship.

That, on the next day, Informant was sent with Ned and four others in the Boat to Green Island with a keg of water for the Natives; and, on the boats approaching the shore, they made a rush

to get into it; the people in the boat shoved off to prevent them, and returned to the Party on shore, when four fresh hands got into the Boat, taking with them two Guns and two Swords and again went to the Island, and one Man got out to take a keg of water on shore; the Natives making a rush to get into the Boat, the Europeans resisted by striking them with their Oars and Swords; and, finding that they persisted, a Gun was fired with slugs over their Heads to frighten them, which did not answer; when a second shot was fired the Informant saw one of them fall forwards on his Face in the Water and the Blood spouting out from both his sides.

Kirby, who steered the boat, fired the first shot, but Informant cannot tell who fired the second.; the Boat was then shoved off and went to the Shore, and the next Morning Randall went again to the Island, and at first the Natives hid themselves; but on seeing Randall who was a great favourite with them, they came out and kissed him; he then took the four into his Boat, leaving the dead Body on the Island, and left Oyster Harbour and landed the four Natives on Michaelmas Island, and left them making great lamentations; Randall then went to Breaksea Island where the other Boat joined, bringing with them the Two Female Natives that they had taken away from the Main Land at Oyster Harbour.

One of these Females is now at Eclipse Island with Samuel Bailey, also a native Girl, a child Seven year old; the other Female taken from this is with George Magennis with the Boat to the Eastward; and this Informant further states that these men have other Native Women that they take about with them, Two from Van Diemen’s Land taken in Bass Strait and one from the Main Land opposite Kangaroo Island.

The Mark of X WILLIAM HOOK

Witness: - E. Lockyer, junr.

Sworn before me: - E. Lockyer, J.P., Major, H.M. 57 Regt.

William Hook

One evening in October 1826, William Hook and seven of his crew mates rowed a whaleboat from Breaksea Island to come alongside the French expedition ship Astrolabe. Captain d’Urville offered them the night aboard and a dinner of ship’s biscuits and brandy. That night the sealers told of how they’d been treated abominably by their employers who had not returned for them, and how they were now living from their fishing and quite destitute.

D’Urville observed William Hook:

A young man with a very swarthy complexion, a broad face and a flat nose looked to me a completely different type from the English; I soon learned, on questioning him, that he was a New Zealander, a native of Kerikeri, attached for nearly eight years from a very early age to the miserable lot of these vagabonds. He speaks English and seems to have completely forgotten his homeland. (176)

Six months later William Hook’s name appeared in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser and he became a public player in the colonial history of Australia. (177) In January 1827, one week after Major Edmund Lockyer’s busy pacifications of Menang men aggrieved by the sealers’ actions, a sealers’ boat approached the Amity asking for provisions. Lockyer let them aboard the Amity for the night and, suspecting the sealers were responsible for the murder of man on Green Island, interviewed them the next day. On the 12th, William Hook made his statement to Lockyer, testifying that he had been present at the Green Island killing and had witnessed the kidnapping of two Menang women. (178)

Although William Hook did not say in his statement who had fired the fatal shot, Lockyer concluded in his correspondences to the Colonial Secretary that it was Samuel Bailey who had assisted in the “atrocious murder” (179), the only evidence being that William Hook declared that Samuel Bailey was present on the boat at the time. When Festing brought Samuel Bailey back from Eclipse Island with the two captured Noongar females, Lockyer arrested Bailey. He then sent Samuel Bailey to Sydney and sent William Hook to testify against him. Once in Sydney, William Hook testified to an examining officer that Samuel Bailey had not shot the man on Green Island, which led to all charges being dropped. (180)

Lockyer and d’Urville’s accounts and descriptions are all I am able to find on the young Maori sealer. After Bailey’s charges were dropped in Sydney, William Hook’s name disappeared from official records. However to gather an estimation of his actions and character, I have sought information ‘around’ William Hook. I have also made tentative links between Hook and other Maori sealers on Bass Strait.

In 1824, John Boultbee kept a journal of his sealing expedition through Bass Strait. In the Hobart Town Gazette, the fellow crew of Boutlbee’s schooner Sally were named as: “Mr A. Hervel, Mr Smith, James Duncan, Robert Robertson, William Aldridge, John Richardson, George Belsey, Tiger New Zealand (a boy), Billhook (a boy) and John Smidmore.” (181)

John Smidmore was present at the killing of the Menang man on Green Island, two years after he worked with Boultbee on the Sally. In fact, after Samuel Bailey was transported to Sydney with William Hook, John Smidmore admitted to Lockyer to shooting the man himself. It is a leap of pure speculation that one of the boys aboard the Sally with John Smidmore in 1824 was William Hook: Tiger, described in Boultbee’s journal as a teenage Maori, or the boy called Billhook – a name that could easily be made official by extending it to William Hook. Aside from my ‘leap’ it is still likely that William Hook worked in Bass Strait or on Kangaroo Island, as those sealing grounds were where most of the Hunter and Governor Brisbane sealers were based before travelling to the west.

It is also likely that when William Hook first arrived in Sydney, he did so through the auspices of one Samuel Marsden. Samuel Marsden had set up New Zealand’s first Christian mission station in William Hook’s home of Kerikeri in 1814, buying five thousand acres from Nga Puhi Chief Honi Hiki “for the princely sum of forty eight axes,” (182) setting up the mission at around the same time that William Hook was a child there. Marsden appears to have engaged in a firearms trade with Honi Hiki, who was interested in gaining ascendancy over other tribes in the area.

Marsden brought Maori children to Australia. He “confided to Pratt that he intended to bring back from New Zealand to Parramatta a number of ‘children of the chiefs’ for education.” (183) Samuel Marsden took the Kerikeri children to his Native Institution in Parramatta (where Fanny was placed in 1827), using the excuse of ‘education’ in what was ostensibly holding Maori children hostage in return for favorable treatment from their parents and to ensure that no harm came to his missionaries in New Zealand.

Another way that William Hook may have crossed the Strait was by being sent out as an adolescent by his family for seafaring, agricultural and cultural experience, or even to earn money to purchase muskets in Sydney. As Dieffenbach wrote in the 1840s, “This spirit of curiousity leads [Maori] often to trust themselves to small coasting vessels; or they go with whalers to see still more distant parts of the globe.” (184) Maori were traditional voyagers and had excellent reputations as seafarers among the European and American sealing and whaling. In the early years of New Zealand offshore whaling and sealing, young Maori were sometimes ill-treated aboard ships; flogged, humiliated or abandoned thousands of miles from their homes. To be fair, some captains treated their crew with absolute equality. Ill treatment by their employers was by no means confined to Maori seafarers, as I have demonstrated previously by outlining the actions of the captains of the Hunter and Governor Brisbane, who abandoned all of their crew, never to return for them. But many young Maori were sent to sea by parents who ranked highly in Maori society. Events such as the burning of the brig Boyd in 1809 alerted colonial administrators to the Maori ‘ship’s boys’ who may have been vulnerable to abuses of power, but were also connected to powerful hierarchies within Maori societies, and that abuses of mana and dignity could be met with terrifying consequences.

The history of post-contact Kerikeri, of young Maori seafarers in the nineteenth century and of the company that William Hook may have kept in Bass Strait gives an indication of the cultures which William Hook lived and worked within. His connection with Samuel Marsden is interesting for several reasons, including that, as a child, he would have interacted with other Europeans and with Christianity far earlier than Maori from other parts of New Zealand. He was a young Indigenous man who successfully straddled cultures, ethnicities and cultural values during the trans-Tasman colonisation. What especially intrigues me about William Hook is that his statement to Lockyer in 1826, whether or not coerced, does not answer to an assumedly tight allegiance to his fellow sealers, especially Samuel Bailey, during the crew’s time of extreme isolation and stress. Yet, it was John Smidmore, the sealer who had possibly worked with Hook before in Bass Strait, who later confessed to shooting the man on Green Island and Hook does not mention him once in his statement.

References:

176. Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 32.

177. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20/04/1827, p. 3.

http://newspapers.nla.gov.au/ndp/page/495597 (accessed 12/08/09)

178. See Appendix 1

179. H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 474.

180. See Appendix 4

181. Beggs, A., & Beggs, N., The World of John Boultbee, Whitcoulls Publishers, Christchurch, 1979, p. 53.

Hobart Town Gazette, 20/08/1824, p. 4.

182. Brook. J., and Kohen, J.L., 1991, p. 135.

183. Brook. J., and Kohen, J.L., 1991, p. 139.

184. Dieffenbach, E., Travels in New Zealand (2 vols) John Murray, London, 1843, in The Prow http://theprow.org.nz.maori-and-whaling/ (accessed 09/03/12)

operations. “Captains and mates relied on their cheap labour, sobriety and skill as harpooners and topmen.”

185. Chaves, K.K., ‘Great Violence Has Been Done: the Collision of Maori Culture and British Seafaring Culture 1803-1817’, in Great Circle, Vol. 29, No. 1, p. 26. See also Pricket, N., ‘Trans-Tasman Stories: Australian Aborigines in New Zealand Sealing and Shore Whaling’, in Terra Australis, ANU, Australia, 2008.

186 Chaves argues that the Boyd massacre resulted from Maori seamen aboard the whalers being treated disrespectfully. Chaves, K., Great Circle, p. 22.

Kaurna Sal

Sally was from the Kaurna people, from the mainland adjacent to Kangaroo Island, in the Gulf of St Vincent, south of what is now called Adelaide. The Astrolabe’s Officer Gaimard recorded the first known word list of Kaurna language, using Sally and her countryman Harry as informants in King George Sound, 1826. (95)

Given evidence of other sealers’ raids in the area, it is probable that Sally’s arrival on Kangaroo Island was not the result of a reciprocal arrangement between her family and the Kangaroo Island sealers like some that occurred in Van Diemen’s Land. Resident Islanders’ forays on the mainland for women were regular, brutal and created political animosity between Kangaroo Islanders and Indigenous peoples.

To illustrate the circumstances of how Sally arrived on Kangaroo Island and what her life there may have been like, I give the following examples of women taken by Kangaroo Islanders:

Albert Karloan, a Yaraldi man from the lower Murray, told the Berndts in the late 1930s that sealers had caught a Ramindjeri woman from near the mouth of the Inman River. She had had a child with her, but they left it on the mainland. “Then they took her to Nepean Bay, where she was ‘passed around the camp’. After this horror, she had managed to crawl away exhausted. She hid that night and most of the next day. When she had rested enough, she swam across the strait and recovered her child.” (96)

In ‘The Booandik Tribe of South Australian Aborigines’, women tell the story of two women who were collecting shellfish on the shore at Rivoli Bay and surprised by some white men who came ashore. The woman who stopped to pick up her child was captured and taken away. Three months later she escaped when the same boat put in at Guichen Bay and she returned “to find her country women lamenting her loss. She did not give a very favourable account of the treatment she received from the crew. Even as late as 1846, the black women, in speaking of this event make all sorts of grimaces, signifying disgust.” (97)

When the Rapid Bay woman Kalloongoo was taken to Flinders Island after several years on Kangaroo Island and Bass Strait, she gave the following testimony to G. A. Robinson. I have quoted a large section here to show what Sally would have experienced, from her abduction to her life on Kangaroo Island.

The woman states that at the time she was seized and torn from her country, Allan the sealer was led or guided to her encampment and where her mother and sister then was by two blackfellows her countrymen but not her tribe and who had been living with the sealers on the island [Kangaroo Island].

Said the blackfellows came sneaking and laid hold of my hand; the other girl ran away. The white man put a rope around my neck like a dog, tie up my hands. We slept in the bush one night and they then tied my legs. In the morning we went to the boat. They took me then to Kangaroo Island.

She remained there a long time until she was brought away in the schooner [Henry owned by J. Griffith] to the straits. She said there were several New Holland [mainlander] black men on Kangaroo Island. Said two of them died from eating seal; her brother died also from eating seal. Said the sealers beat the black women plenty; they cut a piece of flesh off a woman’s buttock; cut off a boy’s ear, Emue’s boy. This woman [Emue] is now on Woody Island with Abyssinia Jack. The boy died in consequence of his wounds. They cut them with broad sealer’s knives. Said they tied them up and beat them and beat them with ropes. Bill Dutton beat her plenty. Said the sealers got drunk plenty and women get drunk too. Said the country where she came from was called BAT.BUN.GER. (98)

Sally sailed to King George Sound with either James Everett or John Randall in 1826. When they met with the crew of the Astrolabe, the officers Quoy and Gaimard described her and her countryman Harry as not being disguised by the ochre that the Menang people smeared over their bodies but with “black, their skin was very smooth, their hair long, black and smooth.” (99) D’Urville was less detached in his journal, writing that Sally was “quite well proportioned” and possessed “rather beautiful eyes.” (100)

Sally stayed in King George Sound with Dinah, Moonie and twelve sealers, until they were taken to Sydney aboard the Ann in May 1827. It is not recorded whether the Ann stopped at Kangaroo Island or whether Sally disembarked at Port Dalrymple with Dinah and Moonie.

However, it is definitely recorded that Sally was living on Kangaroo Island in 1831, having participated in an extraordinary interaction that gives a picture of her strength of character.

Sal is documented in an extract regarding the death of Captain Collet Barker. Barker had just completed his post as the fourth Commandant of King George Sound and was sailing east on the Isabella when they stopped at the Murray River mouth. Barker, wanting to explore, had stripped naked, strapped a compass to his head and swum the Murray River. He climbed over a sixty foot sand dune and was not seen again by his friend, assistant surgeon Robert Davis.

Barker had apparently been stalked and speared to death by three men. It was speculated by the Europeans that the spearing was in retaliation for the Kangaroo Islanders killing and abducting Kaurna people, and that Barker’s naked, white body was to them fair game.

Although Barker’s crew did not see the murder, they knew he’d been attacked and the only men who could swim refused to cross the river, because they could see the warriors and their spears on the other side. Davis sought assistance from a group of Aborigines at Cape Jervis. Here, the crew from the Isabella recognised Sally as one of the women who’d been in King George Sound four years previous. She suggested that they sail to Kangaroo Island and seek help from the resident sealers to find Barker or retrieve his body. On Kangaroo Island, Sally led Robert Davis to a party of sealers on the island and two of them agreed to provide their services as guides. Together with Sally, her father Condoy and another Encounter Bay man, they sailed back to the mainland. They then constructed a traditional reed raft to cross the Murray River and contacted the local people. (101)

The theory that Barker was killed due to the Aborigines’ fear and hatred of the Kangaroo Islanders is complicated by the fact that two Kangaroo Islanders acted as negotiators between the same Aborigines and the Isabella crew. Robert Davis wrote in his report that the sealer George ‘Fireball’ Bates was essential for obtaining the information of the circumstances of Barker’s death, due to the “knowledge he possessed of the language and manners of the natives.” (102)

But the death of Captain Collet Barker also lends to an interesting discussion of a cross cultural communication between sealers, colonial military and Aboriginal women. Although Sally was probably abducted during an Encounter Bay raid and imprisoned on Kangaroo Island for several years; after travelling to King George Sound in 1826 she became trusted by the Commandant’s men and by the Kangaroo and Breaksea Islanders, plus she was also still able to maintain a utilitarian relationship with her country men and women.

Between Sally, her father, George Bates and the other Kangaroo Islanders, they ascertained the names of Barker’s killers. The three spearmen were named as Cummaringeree, Pennegoora and Wannangetta. Davis paid the Kangaroo Islanders twelve pounds, one shilling and sixpence and commended one of them in his report to the Governor, then gave the receipt to those officers handling the ex-Commandant’s affairs. (103)

References:

95 Rob Amery, ‘Kaurna language (Kaurna warra)’, SA History Hub, History SA, http://sahistoryhub.com.au/subjects/kaurna-language-kaurna-warra, accessed 2 July 2014. See also, Amery, R., Kaurna in Tasmania: A Case of Mistaken Identity’, in Aboriginal History, Vol. 20, pp. 24-50, 1996, p. 45.

96 Taylor, R., Unearthed: The Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island, Wakefield Press, South Australia, 2002, (2008), p. 41.

The Backstairs Passage between Kangaroo Island and mainland Australia is roughly thirteen kilometres.

97 Smith, J., ‘The First Ship at Rivoli Bay’, in The Booandik Tribe of South Australian Aborigines, E. Spiller, Government Printer, Adelaide, 1880, p.25. Available from

https://archive.org/stream/booandiktribeso00smitgoog#page/n7/mode/2up (accessed 06/06/2014).

98. Amery, Rob, 1996, ‘Kaurna in Tasmania; A case of mistaken identity’, p. 41. (BAT.BUN.GER translated as Patpangga, or Rapid Bay, to the south of what is now called Adelaide.)

99. Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 45.

100. Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 34.

101. Mulvaney, J., & Green, N., Eds., Commandant of Solitude: The Journals of Captain Collet Barker 1828-1831, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 1992, p. 25.

102. Robert Davis in Taylor, R., 2002 (2008), p. 63.

103. Mulvaney, J., and Green, N., Eds., 1992, p. 26.

Fanny Bailey, Tama Hine, Weed

Child labourers in the 1800s

Recently I talked to a senior social worker about the little girl who Lockyer had removed from the sealer Samuel Bailey in 1827. “I’ve often thought that it was the first child protection case in Western Australia,” he said, “and you know what? The same dilemmas that Lockyer faced still apply today – if she has no parents or carers, then where do I send this child to keep her safe?” (58)

As well as the abducted Menang woman whom he’d ‘drawn a straw for’; Samuel Bailey took a six or seven year old child to Eclipse Island. Fanny (59) was an Aboriginal girl whom d’Urville described as being “from the mainland opposite Middle Island.” (60) There is a paucity of records regarding her origins. Lockyer mentions vaguely that she hailed from “the mainland Eastward of this.” (61) D’Urville noted that although the other women had been with the sealers for several years, the child had only been with them for about seven months. (62) Given that the Governor Brisbane or Hunter crew had been left at Middle Island seven months previous to meeting d’Urville in King George Sound, it is most likely that they took Fanny from the Esperance area.

Whether Fanny was the daughter of an Aboriginal woman who had been taken by sealers, or abducted alone from the mainland is uncertain. There are no records of adult Noongar women living within the Breaksea Island community of 1826 other than the two Menang women who were kidnapped in King George Sound. I posit that Fanny was kidnapped alone and that her abduction was one of the earliest actions of the Governor Brisbane or Hunter crew when they were dropped at Middle Island.

Bass Strait sealers, or Straitsmen, kidnapped both male and female Pallawah children, as did the Vandemonian settlers. (63) The children were used as a labour source and as concubines for those of paedophilic tendencies. Nicholas Clements writes that female Pallawah children were especially vulnerable to abduction: “For one their inexperience and lack of strength made them more vulnerable in ambushes. Taken young, they were also more likely to grow submissive, and if prepubescent, they would not burden their masters with unwanted children. What is more, they would hold their value as labourers and concubines longer.” (64)

Straitsmen also often kept their own offspring after their Tyreelore mothers had died, been sold to a sealer on another island, or been taken by the ‘conciliator’ G.A. Robinson into exile at Gun Carriage Island and later Flinders Island.

Samuel Bailey, according to William Hook’s testimony, took Fanny and the Menang woman to Eclipse Island some time during October or November 1826. There is a (now abandoned) lighthouse settlement on the island these days but it is still a wild and isolated place. Bailey would have worked the rocks and nearby Seagull Island for seal, salted the skins and tried out the oil. He would have expected the two females to work for him. He may have taught them. It was dangerous working those rocks in rough seas. Eclipse Island, bearing the brunt of the Southern Ocean, its steep granite cliffs on the south side scarred by wind and sea, is a dangerous place to work at any time of the year.

While Bailey was at Eclipse, the Amity arrived. When William Hook informed Lockyer of the girl and woman being held captive on Eclipse Island, Lockyer sent a boat out to Eclipse Island to rescue them and arrest Samuel Bailey. On the morning of the 13th of January, Menang people began gathering at Lockyer’s makeshift garrison to await their return. Lockyer pointed at the sun and drew a line to the western horizon to explain that they would have to wait until early evening before the boat returned. In his report he expressed his apprehension as to whether the boat would even get back that night and whether the Menang woman would be in it. (65)

At sunset the boat came in through the heads and moored close to where the Residency Museum is now situated. The horror of what the Menang woman and Fanny had endured during the weeks on Eclipse Island was evident to everyone who saw them. The Menang woman was greeted with tears and consternation by her country men and women. But the people who greeted her also indicated that Fanny did not belong with them. “The natives looked upon the little Girl and shook their heads, meaning she did not belong to them and then pointed to Pigeon and then to the Girl meaning that he must take care of her.” (66)

At this point, Lockyer gave the child a name, Fanny. He possibly thought of his own daughter Fanny Oceana, who was roughly the same age as the child. (67) Lockyer later decided to send Fanny to New South Wales on the Amity’s return trip. The Governor would decide what to do with her. D.A.P. West theorises that this action indicated a lack of European female presence in the settlement to care for Fanny (68) however records show that three women and two children arrived on the Amity and were living in the settlement. (69) Perhaps Fanny was considered a burden, an extra mouth to feed in a fledgling colony already grappling with the spearing of their only blacksmith, feuding sealers and natives, and the death of three sheep. Perhaps it was protocol to send all Aboriginal foundlings to New South Wales. Perhaps Lockyer despaired of any other alternative. I wonder at how visibly abused she was and whether Lockyer suspected that she had been raped by Samuel Bailey and I think about what the social worker said to me.

Lockyer wrote in his report, “As the Amity is set to sail on Tuesday, I have ordered that the little Girl Fanny who was taken off the mainland to the Eastward of this, and having no means of restoring her to the tribe to which she belongs, to be taken to Sydney for the disposal of His Excellency.” (70)

On the 24th of January, Fanny left King George Sound for Sydney in the company of Samuel Bailey and William Hook, who was to testify against Bailey on arrival. Samuel Bailey was aboard as a prisoner to be interviewed about his involvement in the Green Island murder. There were no women aboard the ship. Although Fanny had spent several months in small whaleboats, this was the first time that she had sailed on a brig. By the time she arrived in Sydney, authorities named her Fanny Bailey, after her abductor.

In February 1827, Fanny was taken to the Aboriginal School at Blacktown by the captain of the Amity Thomas Hansen. (71) Maori, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children learned reading and writing at the school in racially segregated classes. The boys worked at carpentry and the girls at sewing and knitting. Samuel Marsden established the school under the colonial ideology of ‘Civilise, Commercialise, Christianise.’ When the school ran short of its quota of Aboriginal children volunteered by their parents, Marsden was known to ‘obtain’ residential students in order to fulfil his ideology of assimilation and civilisation. (72)

“There are obvious discrepancies regarding Fanny Bailey’s origins,” wrote the biographers of the Parramatta Native Institution. “Whatever, she must have been awfully bewildered and confused by the time the changing events of her few years of life drew her under the guidance of William and Dinah Hall (73) at the Native Institution. Bemused, she received two ‘shifts’ of her own and was placed on rations at Black Town on March 10 1827, so becoming the fifteenth student.” (74) This quote below from The Parramatta Native Institution and Black Town, a history illustrates how Fanny’s life changed from one of violence, disorder and exile with the Breaksea Islanders to routine, confinement and exile at the Native Institution:

1. Children to be up and dressed by 6. And set to work.

2. To wash themselves at ½ past 7, go to prayers and breakfast at 8.

3. To work until 10 o’clock.

4. To wash and go to school from 10 until 12. Write one copy, read ½ an hour, cipher I hour.

5. To dine at ¼ after 12 and play till 1.

6. To school at 1. Read and cipher until 2.

7. To work from 2 till 6, the boys at carpenting, the girls sewing and knitting.

8. To play and wash and ready for supper at 7.

9. To prayers at ½ past 7 and to be in bed at 8.

10. On Sunday, morning to be devoted to instruction of church service.

Breakfast: 1 quart of Maize meal, sugar and milk. Dinner – Beef soup, meat with rice or meal, vegetables, and for supper, Bread and Tea. (75)

At seven years old, Fanny had been kidnapped by strangers and taken away from her family. She spent nine months sailing between islands of the south coast with a strange and desperate community of Aboriginal women, hunting dogs and men from all over the world. They would have smelt of seal oil and fish. She may have been used by the men for sex. The women would have taken Fanny hunting for seal with them, lurching into rocky shores lined with toothy barnacles, the thump of club on the seals’ skulls, eyes without skin around them. They sailed hundreds of nautical miles, island hopping from the Archipelago, to Doubtful Islands, to King George Sound in a twenty foot whaleboat. On the journey, Fanny would have slept on piles of skins and canvas in the boat, or camped on the north facing side of the islands. She would have seen the Astrolabe get blown past Breaksea Island and return in the morning, the rigging crawling with men in hats and white shirts. The captain, a florid, robust white man would have looked at her intently when she pulled alongside the ship with the sealers. He spoke to the Maori and nodded her way. Later Fanny must have seen the Menang women brought out to Breaksea Island, bruised, bleeding and tearful, their hands tied behind their backs.

When Samuel Bailey took Fanny to Eclipse Island, the weather was foul with wild spring gales and huge seas. (76) The Menang woman wouldn’t swim and did not know how to handle a boat. Once again, the two girls were trapped on an island by a man. Sometimes they would have seen the hunting fires from Mokare’s family domain at Torndirrup on the mainland. (77) They would have eaten the greasy muttonbirds and fish and wild celery and any of the yams and tubers that they recognised, and slept, curled together for warmth. Bailey had plenty of brandy that he had gained trading the women’s hunting efforts with the Frenchmen. When he was drinking, Fanny and the Menang woman must have roamed the island, keeping out of his way. Then the Menang woman’s arm was broken.

After being rescued by Lockyer’s lieutenant, Fanny’s fate was again directed the decisions and actions of strangers. Although I have not found records relating to Fanny Bailey after she was enrolled at the Native School, it is likely that if she survived the Native Institution, this control over her agency as an individual would have continued for the rest of her life.

A teacher from the school, Elizabeth Shelley giving evidence before the Committee on the Aborigines Question in 1838 said that she found many ex pupils had “relapsed into all the bad habits of the untaught natives. A few of the boys went to sea.” As for the girls, most of them “turned out very bad” with the exception of one who had married a white man. Frequently the ex-teacher had conversed with the girls on religious subjects but they only laughed and said they had “forgotten all about it”. (78)

57 Plomley, Ed. 2006, p. 335.

58 Travers, C., pers. comm. 11/06/2014.

59 For the purposes of identification I use the name ‘Fanny’ for the girl, as Lockyer named her in Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 472.

60 Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p. 32.

61 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 473.

62 Rosenman, H., Trans. Ed. 1987, p.76

63 “1816 – 1818: Kidnapping of Aboriginal children becomes widespread. Government notices continue to outlaw the practice, to no avail.” Ryan, L., ‘List of multiple killings of Aborigines in Tasmania: 1804 – 1835’, Online Encyclopaedia of Mass Violence, http://www.massviolence.org/List -of-multiple-killings-of-Aborigines-in-Tasmania-1804 (accessed 10/10/2011).

64 Clements, N., The Black War: fear, sex and resistance in Tasmania, University of Queensland Press, Queensland, 2014, p. 194.

65 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 470.

66 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 470.

67 “Amongst the Major's other children was daughter Fanny Oceana Lockyer, born at sea in the Bay of Bengal on October 17th, 1817. She was nine at the time of the command.”Lynch, C., A View from Mt Clarence, http://theviewfrommountclarence.blogspot.com.au/2014/04/the-majors-butterflies-finally-beat-him.html, (accessed 15/06/2014).

68 West, D.A.P., The Settlement on the Sound, West Australian Museum, 2004 (1976), p..58.

69 Sweetman, J., The Military Establishment and Penal Settlement at King George Sound, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1989, p.1.

70 Lockyer, H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 472.

71 Hansen, K., 2007, pp. 23-24.

72 “The process of removal of children from their parents, in order to fill the Native Institution, was a major contributing factor to the lack of support for the Institution by the local Aborigines.” Brook, J., and Kohen. J. L., The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town. A History. New South Wales University Press, New South Wales, 1991, p. 263.

73 William Hall in Marsden’s words was “one of the wore out missionaries from New Zealand.” Hall’s appointment to the school was apparently Marsden’s strategy to rest Hall from New Zealand but avoid paying Hall his retirement fund from the Christian Missionary Society. Brook. J., and Kohen, J.L., 1991, p.179.

74 Brook. J., and Kohen, J.L., 1991, p. 212.

75 Brook. J., and Kohen, J.L., 1991, p. 206.

76 As communicated by sealers to Lockyer. H.R.A. III, Vol. 1, p. 484.